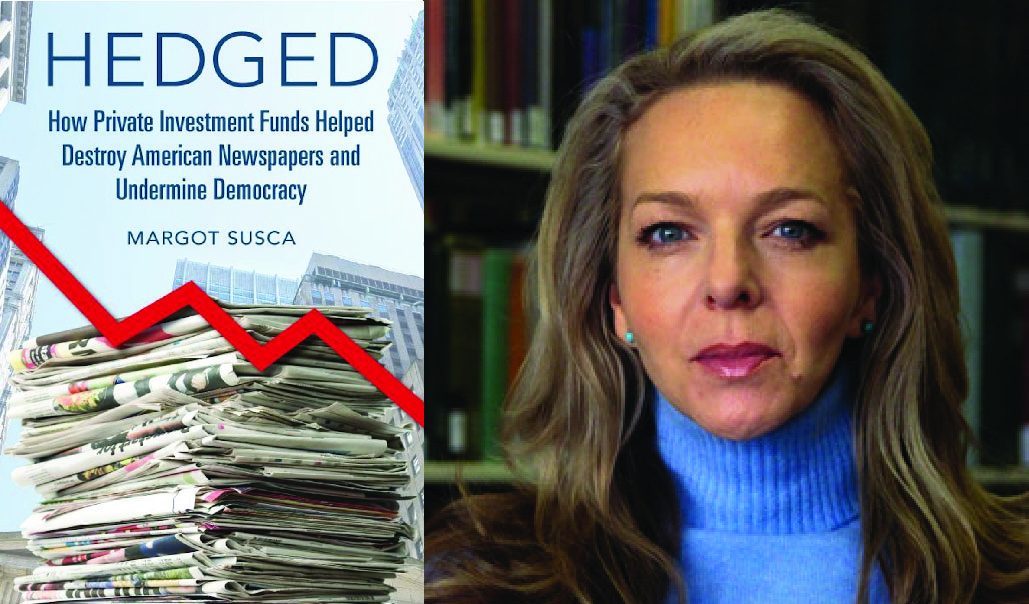

A Q&A with Margot Susca

By Abby Youran Qin

There’s the familiar story about the decline of local news: the internet arrived, audiences left and newspapers slowly faded. But Margot Susca’s book reveals a far more unsettling reality — local newspapers were hollowed out long before digital disruption fully arrived. According to Susca, decades of mergers, towering debt and owners who treated newsrooms as financial assets rather than civic institutions set the stage for today’s crisis.

What remains is a newsroom workforce trying to serve democracy from inside institutions that often work against them. In this Q&A, Susca, an assistant professor of journalism, accountability, and democracy at American University, unpacks how we got here, what financialization looks like in local journalism and how journalists can navigate the contradictory demands of democratic labor and corporate control.

Financialization of Journalism

Local news didn’t collapse overnight. It unravelled through a chain of business decisions —mergers, debt and financial takeovers — that slowly turned community-serving institutions into financial assets. I began by asking Margot Susca to walk us back to where the unravelling started, with mergers.

It all started with mergers.

Q: Your book shows that the crisis in local news didn’t begin with the internet alone, but with a wave of mergers and acquisitions. Can you elaborate on that?

A: When I went through the bankruptcy filings and corporate records, it became clear that the crisis began long before social media.

As the internet grew, newspaper executives feared losing advertising to Craigslist, Monster.com, eBay and other early digital competitors. So they chose mergers and acquisitions. The idea was: if we get bigger, we’ll be safer. A larger company, the thinking went, would be more insulated from advertising losses and from digital competitors.

But that logic didn’t hold up. Mergers rarely create value, we know this across industries.

In late 1990s and early 2000s, newspapers still dominated local advertising markets and were earning strong profits. They had every opportunity to innovate in the digital space. Instead, they chose scale and debt. Bankruptcy documents show almost no meaningful digital strategy. These companies were trying to grow their way out of the problem rather than adapt to it.

Mergers created debt. Debt created an opening for financial actors.

Q: So what happened after the mergers?

A: Those media companies were still profitable, outperforming the S&P 500 in the early 2000s. But they financed their mergers with enormous loans. The Knight Ridder–McClatchy deal alone was billions of dollars.

It’s like taking out a luxury-car loan on a tight budget: you might be stable before, but that kind of debt can sink you. When advertising dipped and subscriptions fell — partly because coverage was already getting thinner — these companies simply could not service their merger debt.

Bankruptcy followed. And bankruptcy opened the door to hedge funds and private equity firms. They bought the debt at a discount, converted it into ownership, and in some cases profited by trading the debt itself. Newspaper debt essentially became a market. That’s the heart of financialization.

The top three newspaper chains, USA Today (formerly Gannett), Lee and Digital First are all heavily influenced by institutional investors. Together, they own over half of the country’s major daily newspapers.

Newsrooms under financialized ownership: “It’s as if they don’t want the work to be done”

Q: Can you briefly explain what private equity firms and hedge funds did to newsrooms?

A: From the newsroom’s perspective, the outcomes of hedge-fund and private-equity ownership often look similar.

- Private equity usually targets privately held or family-owned companies. They install their own management and aim to extract profits over a longer horizon, typically eight to ten years.

- Hedge funds often target publicly traded companies, buy debt cheaply and convert that debt into equity during bankruptcy.

Both models rely heavily on borrowed money. Both treat newspapers as financial assets, not civic institutions. And both have had devastating consequences.

They lay off journalists, consolidate copy desks and production, move newsrooms to the margins of the communities they serve and sell off office buildings for quick cash. Those short-term gains don’t go back into journalism — they’re funnelled upward as management fees and shareholder dividends.

If I were rewriting “Hedged” today, I would devote even more attention to Fortress Investment Group, the private equity firm behind what is now the USA Today network (formerly Gannett and GateHouse). The management fees and extractions they took — while local newsrooms were being gutted — were, in my view, an American tragedy.

A telling example from the book: during COVID, an investigative reporter at a McClatchy paper asked for Microsoft Excel. The hedge-fund-owned company said no.

It’s as if they don’t want the work to be done.

Once you cut a newsroom from 100 journalists to 20, you cannot cover a community. People notice the decline, subscriptions fall and a downward spiral begins: worse journalism → audience loss → more cuts → even worse journalism.

This isn’t a story of the internet killing newspapers. It’s a story of financial extraction hollowing out public-service institutions.

Ethical Labor in Broken Institutions

After mapping how institutions were hollowed out, I asked Susca about the people still working inside them, journalists who continue trying to serve the public under owners who often hinder the work.

“I won’t help you kill newspapers” — why journalists feel conflicted

Q: In your book, you mentioned a former colleague who emailed you, “I won’t help you kill newspapers.” At the same time, many journalists you interviewed clearly understand the harms financialized owners are causing. How do you make sense of these conflicting feelings?

A: For so long, journalists were taught not to think about ownership. In the newsrooms where I worked, advertising and editorial were literally in separate spaces. We were told, “Don’t cross that line.” It was meant to protect independence, but it also kept journalists from understanding the business they worked in.

So when you point out that the system is broken, many journalists hear that their work is broken. The colleague who said, “I won’t help you kill newspapers” wasn’t defending hedge funds; he was defending the meaning of his career.

But here’s the truth: We can’t repair journalism unless we understand how our labor is being exploited.

Journalists want to serve democracy — but they are also workers

Q: Many journalists see their work as public service. That can make it hard to advocate for themselves or even recognize exploitation. How do you understand journalists as workers — and what can they realistically do?

A: Journalism is the labor of democracy. But it is still labor. It takes place inside a capitalist system where owners profit off that labor.

When journalists don’t see themselves as workers, they become easier to exploit. They take on workloads that are impossible. They accept low pay, burnout and even the loss of basic reporting tools because they believe the public needs them.

So I give young journalists practical advice:

- Build your own work — a newsletter, a podcast, something you control.

- Look seriously at nonprofit news — some of the best accountability journalism is happening there (e.g., The Lens, Mississippi Today).

- Be open to location — impactful reporting isn’t limited to big coastal cities.

- Learn to negotiate — you can’t do the work if you can’t pay rent.

- Always research ownership — it’s essential for understanding how your labor will be treated.

Journalists can’t single-handedly undo financialization. But they can protect themselves, make informed choices and align their labor with institutions that still believe in public service.

Abby Qin is a 2025 fellow at the Center for Journalism Ethics and a graduate student in the School of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

The Center for Journalism Ethics encourages the highest standards in journalism ethics worldwide. We foster vigorous debate about ethical practices in journalism and provide a resource for producers, consumers and students of journalism.