By Ella Hanley

Don’t rely on law enforcement as a primary source. That’s the first piece of advice Maia Szalavitz has for journalists reporting on drug addiction.

“It shouldn’t be a crime issue in the way that it is,” she said. “An arrest is not a diagnosis of an addiction.”

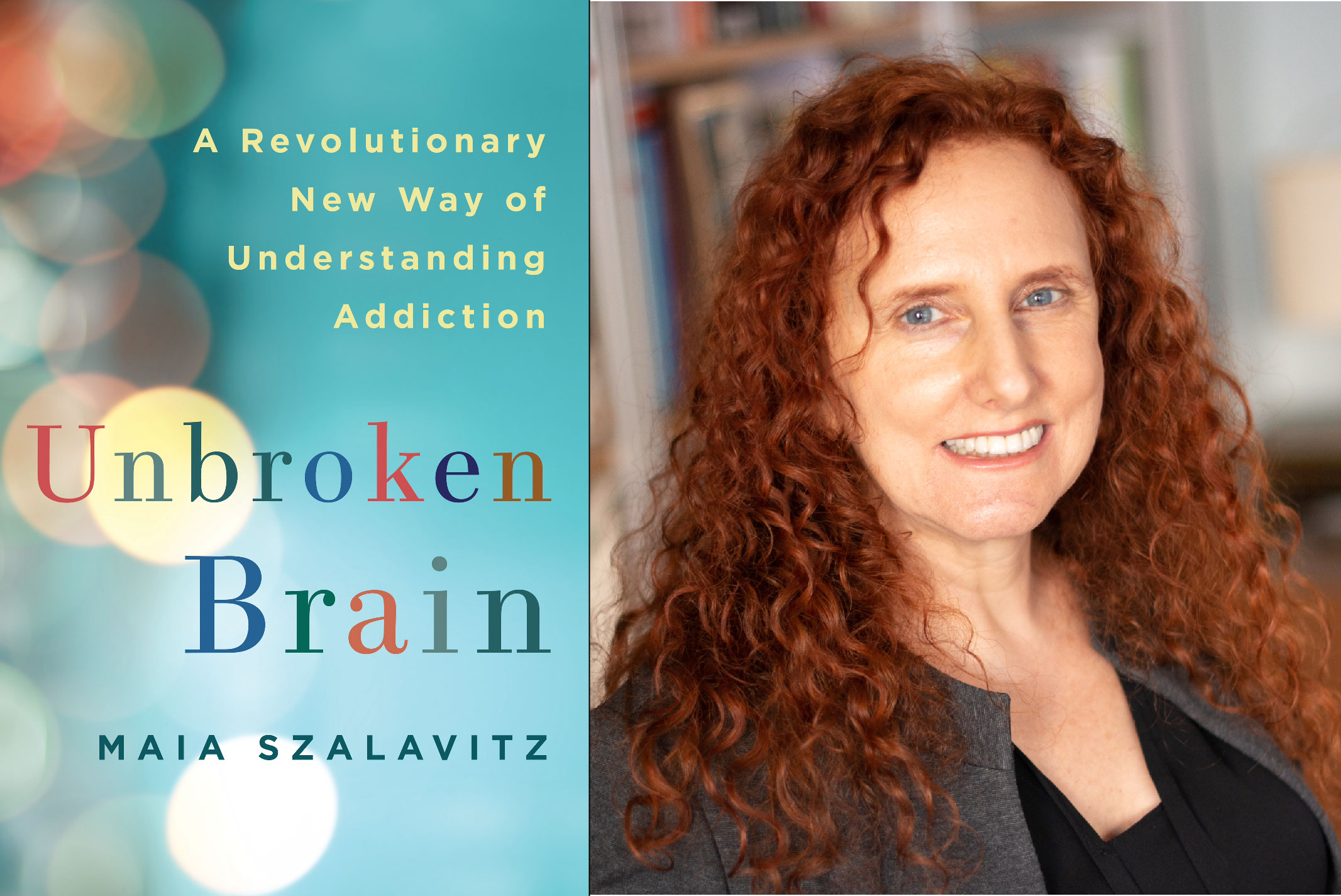

Szalavitz, an award-winning journalist and author specializing in addiction and public health, is the author of “Unbroken Brain: A Revolutionary New Way of Understanding Addiction.” She argues that addiction is best understood as a learning disorder affecting how the brain adapts to experiences.

Framing addiction as a developmental issue rather than a moral failing or criminal problem reduces stigma and opens the door to more effective treatment approaches — a perspective Szalavitz believes should also guide the way journalists cover the topic.

This conversation has been edited for clarity and concision.

What would you say the main consequences of reporting on drug addiction as a criminal issue are for society?

The primary problem with reporting on drugs as a crime issue is that you will most likely be highlighting people in really extreme situations. It replicates this false idea that addiction is a moral problem, it’s about bad people doing bad things, rather than people who have a problem and are searching for ways to solve it with substances that society has declared illegal.

Many people with addiction are trying to solve a problem; they’re seeking a way to live meaningfully in the world. If they have no job opportunities or social connections, why wouldn’t they use something that makes them feel better? There shouldn’t be a notion of innocence or guilt here because addiction doesn’t work that way.

The point here is that people are often saying, “we need the hammer of jail to get people into treatment.” If jail, criminal prosecution and coercion are the best way to get people into care, why are people we enforce the system on the most getting the least care?

What should journalists keep in mind when framing addiction in their reporting, and how might their writing influence public policy or treatment?

The reality is, this is a complicated subject, and it’s really difficult to know a lot about addiction, even if you know everything about the dopamine system and how it works in the brain. Many people have this assumption about drug law that some very good experts sat down and decided some drugs should be illegal based on science, but this is not the case. Our drug laws, all of them, have resulted from a series of moral panics that typically involve racism. That’s an important context.

Another thing reporters should think about is, there’s a bias in this country that recovery means abstinence through twelve-step programs, and everything other than that is kind of suspect. There’s no scientific basis to believe that this is the best or only way to recover. In fact, most people recover from actual addictions without any treatment whatsoever. Misleading reporting can also create a bias against harm reduction, the idea in drug policy that the government should not care if someone gets unearned pleasure from drugs, they should care if that person hurts themselves or anybody else.

Let’s say you go to a syringe service program site and see people who are actively using drugs. Maybe they have horrible wounds and are having some of the worst days of their life, and they look terrible. You’ll think, ‘God, harm reduction doesn’t work. Look at these people.’ But the people who have been helped from the program are gone, they aren’t there because they’ve recovered. Or they are invisible, as people working in the program who look just as healthy as anyone else.

In your book, you describe addiction as more of an emotional learning problem rather than a pure disease or moral failing. How can reporting support that narrative, and what steps can journalists take to frame stories in a way that helps the public understand harm reduction and medically assisted treatment?

It’s so important to look deeper. People need to be allowed to tell their stories, and those stories should be placed in context. It’s overwhelmingly about people trying to feel okay, not seeking extra pleasure. Addiction has been dehumanized; people are often seen as zombies who lose control the moment they use drugs, but that isn’t reality. Very few people deliberately use drugs in front of the police, so clearly they maintain some control over their behavior. I think the key issue is that we fail to distinguish between addiction and dependence. Addiction is compulsive drug use despite negative consequences. It causes harm, and harm is essentially baked into it. Dependence, on the other hand, is just needing something to function. Everybody is dependent on something. We’re dependent on each other — biologically, we relieve each other’s stress. We’re dependent on food, water, air, and so on. Some people are dependent on antidepressants or medications. Dependence isn’t a problem if the benefits outweigh the risks.

What specific language or phrasing is particularly harmful in addiction coverage?

With addiction, if someone wants to say, “I’m a junkie” or “I’m an addict,” that’s their prerogative. But for journalists, derogatory language about any group should be avoided. Members of that group may reclaim or use the language themselves, but as a reporter, you have to handle it with care.

I think it’s important to be precise when talking about people with addiction. The current DSM [Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders] includes the condition “substance use disorder,” but only moderate to severe substance use disorder is actually equivalent to addiction, so mild substance use disorder is not the same. So, if you say “person with substance use disorder,” you risk blurring the issue and creating confusion. While some writers might get away with that phrasing, especially if they’re paid by the word, “person with addiction” is clearer, because people generally understand what addiction is and recognize it as a problem, as opposed to merely using a substance.

Person-first language is important, as is respecting individuals’ preferences. Another caution is to avoid false causal language. People often imply, for example, that starting marijuana led to heroin use, when in fact a third factor usually contributed to both. This is another common problem.

When reporting on drug addiction, it’s often crucial to get a person’s full drug use history. Saying someone “got hooked by a doctor” might sound compelling, but it’s rarely the root cause. If it truly is, then that should be reported. But often the story is more complex: for instance, a football player who previously used cocaine and drank heavily, then suffers an injury and takes opioids, eventually escalating use, can we really say the doctor caused that addiction?

It’s also important to understand the fuller context when people say things like “jail saved my life.” I always ask, “What happened afterward?” Sometimes people say jail saved their life because they are trying to make meaning out of a horrible experience, and in doing so, they end up supporting their own oppression. Instead of acknowledging that incarceration is not an appropriate treatment for medical problems, they feel compelled to frame it as helpful. It’s crucial to respect the person’s narrative, but also to recognize that people often feel pressured to fit their story into the existing, socially accepted narrative.

How can journalists create strong storytelling while avoiding sensationalism or leaning toward crime-centric reporting?

I mean, a little sensationalism isn’t bad. But what you really want is for people to empathize and recognize that these individuals are not behaving in an inhuman, animalistic or incomprehensible way. They are behaving in ways anyone might when faced with what they are facing. Most people, I think, have tried and failed on a diet, or tried and failed to start an exercise routine, or attempted to change any other habit — they understand how hard that is, and that progress doesn’t happen instantly. Most people have also experienced falling in love with someone they cannot be with for whatever reason, still desperately wanting that person despite the impossibility. Addiction is similar, except the object of desire is a drug rather than a person.

Evolutionarily, we are designed to persist despite negative consequences to seek biological needs. Addiction taps into that same persistence, driving behaviors even when the outcomes are harmful, much as we persist in pursuit of a partner or the wellbeing of others.

You also have to talk to people about more than just their addiction — their childhood, their friends, their hopes and dreams or their passions. When you see someone as a full human being, you are much less likely to think, “I want to throw them away.”

In any case, addiction exists on a spectrum. The key is to understand as much of the human as possible and convey that to the reader, so they care about addressing addiction in ways that will actually work. Because, if the default response is just to lock people up, without understanding them or supporting them, nothing changes.

Ella Hanley is a 2025-26 fellow at the Center for Journalism Ethics and an undergraduate student in the School of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

The Center for Journalism Ethics encourages the highest standards in journalism ethics worldwide. We foster vigorous debate about ethical practices in journalism and provide a resource for producers, consumers and students of journalism.